Schools are meant to prepare learners for the future but they are quite often robbed of that until they leave high school.

With the speculative learning method, the idea is to try and have learners invent the future by employing and, in doing so, immediately contextualizing the variety of things they have learned to shape their speculation.

Basically, the goal is to answer the question every student has ever asked which is “why are we learning this?”

Currently the model of learning is all about feeding the learners some facts and then asking them to repeat the facts back.

If they’re lucky, they’ll get to give an opinion on a history paper, or answer state how many apples James have left after Jenny took three.

The problem with this is, as you have likely also experienced from school, the knowledge doesn’t stick and in the worst cases, you lose passion for the subject.

As I wrote before in an article titled ‘deliberate speculation’, I wanted to see if it was possible to extract the exciting elements of the “what if cars could fly?” sort of conversations, and tie them together with something that gives context to the information we are given at school, and more importantly, see if it can empower learners to “reclaim” their future by empowering them to invent it.

We could just say that asking learners “what if cars could fly?”

The problem with that is of course is that while the learners will generate a plethora of possibilities, none of them may lead to anything. What are we learning if we’re just stating fantasies about what would happen if the flying car was invented tomorrow. The lack of context and history, as well as the lack of scientific knowledge, would make those conversations pure fiction — which is excellent, but it’s not the intended effect.

Contextualizing information is already happening in some progressive history classes in Scandinavia, where teachers ask learners to create solutions for problems that happened in history. Another group from Norway named Vitenattempted to solve for relevance by creating an online portal that explored a variety of topics, claiming:

The main aim for all Viten programs is that students should learn about the processes and products of science. Learning science involves being introduced to the concepts, conventions, laws, theories, principles and the ways of working in science. It involves coming to appreciate how this knowledge can be applied to social, technological and environmental issues.

Another group in Denmark created the INDEX · Design to Improve Life which also attempted to add context to learning by:

Design to Improve Life Education is about putting structured creativity on the learning agenda. It is a framework of methods enabling its users to initiate change in society by coming up with innovative solutions to real problems like food waste and climate change.

We can consider using the present and past as a base then and ask the learners our hypothetical questions.

Some problems that have already arisen with these which a teacher from the, beautifully built and highly progressive, Ørestad Gymnasium (high school) in Copenhagen, Denmark has told me is that the students would often get so caught up in speculating that they wouldn’t bother with learning the actual information.

That being said, this isn’t a knock on the those systems — if anything they are further inspiration and proof that speculative methods are needed. They are perhaps just a little out of touch with technology or discount linking previous information with the future too much. Another problem I find is that they are almost too grounded in reality. After all these systems are meant to be engaging people with different attention spans and levels of education.

This brings us to where I am positioning my hypothesis.

My belief is that if we can combine the engaging elements from a “can you imagine if ______” question with a fictional future scenario and a strong history linking mechanism, we can create good conversations that reveal a lot about how learners think and what they want to dive into more deeply as a subject.

Testing out the idea

I decided to test out this idea at the Ørestad Gymnasium, to see how engaging it would be. I only had an hour to explain everything and get feedback, so the exercise was only 10 minutes long.

This was what the exercise set out as a story:

- Suppose the Wright brothers crashed and died during their first test flight

- The Germans win WWII and eugenics succeeds

- A coloured man is being sent to jail in 2100 for reasons he doesn’t understand

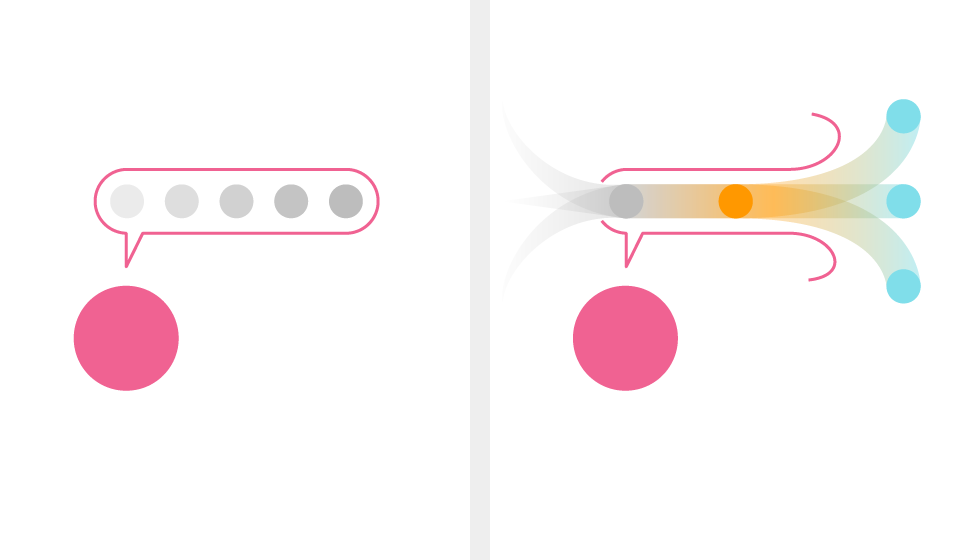

The high schoolers got some time dedicated to research on their laptops and phones and then were given some time to discuss. However, I added a small twist. One person in each group, called a parser, was to record the variety of subjects that each of the others was saying and declare whether what was being said was fact, sentiment, or speculation.

The purpose of the parser was to show the others how many topics they are touching upon in a standard discussion. This was the hook for the context and relevance of topics. The other element was to reveal back to the students some data about how they think, not just a final letter or number based assessment.

Of course, things didn’t go perfectly. While the students found it fun, they didn’t quite see how this could help them improve their grades. The point was never to boost grades, but this just goes to show how institutionalized these things are in our minds. Another problem was that understanding the data about what they were saying was quite abstract as well. The value of the fact:sentiment:sp

eculation ratio was not clear.

On the flip side, some of the students agreed that it’s a good way to warm up the brain before a subject. In addition, the idea that the discussions were speculative and thus undefined in their boundaries outside of the time and conditions of the story, the students liked the idea that they could tackle topics within the constraints that they enjoy, and appreciated that it enable learning for the sake of it and not just to achieve a metric.

This made it clear where I should focus on my work going forward:

- The analysis of the speculative system

- The relevance to a regular school — if there is any at all

- Creating a way for the teacher to create compelling situations that the learners can discuss within

This is a progress update entry in my 7 week final thesis project at CIID. You can read all the other entries here.